Transshipment or Transhipment is the shipment of goods or container to an intermediate destination, and then from there to yet another destination.

One possible reason is to change the means of transport during the journey (for example from ship transport to road transport), known as transloading. Another reason is to combine small shipments into a large shipment, dividing the large shipment at the other end. Transshipment usually takes place intransport hubs. Much international transshipment also takes place in designated customs areas, thus avoiding the need for customs checks or duties, otherwise a major hindrance for efficient transport.

Note that transshipment is generally considered as a legal term. An item handled (from the shipper's point of view) as a single movement is not generally considered transshipped, even though it may in reality change from one transport to another at several points. Previously it was often not distinguished from transloading since each leg of such a trip was typically handled by a different shipper.

Transshipment is normally fully legitimate and an everyday part of the world's trade. However, it can also be a method used to disguise intent, as is the case with illegal logging, smuggling or grey market goods.

Transshipment at container ports or terminals

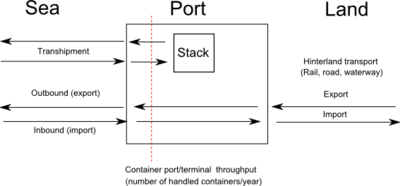

The transhipment of containers at a container port or terminal can be defined as the number (or proportion of) containers, possibly expressed in TEU, of the total container flow that is handled at the port or terminal and (after a temporariliy storage in the stack) transferred to another ship to reach their destinations. The exact definition of transhipment may differ between ports, mostly depending on the inclusion of inland water transport (barges operating on canals and rivers to the hinterland). The definition of transhipment may:

- include only seaborne transfers (i.e. a change to another international deepsea container ship)

- include both seaborne and inland waterway ship transfers (sometimes indicated as water-to-water transhipment). Most coastal container ports in China have a large proportion of riverside 'transhipment' to the hinterland.

In both cases, a single, unique, transhipped container is counted twice in the port performance, since is it is handled twice by the waterside cranes (separate unloading from arriving ship A, waiting in the stack, and loading onto departing ship B).

[edit]

Cross-docking:

Cross-docking is a practice in logistics of unloading materials from an incoming semi-trailer truck or rail car and loading these materials directly into outbound trucks, trailers, or rail cars, with little or no storage in between. This may be done to change type of conveyance, to sort material intended for different destinations, or to combine material from different origins into transport vehicles (or containers) with the same, or similar destination.Cross-Dock operations were first pioneered in the US trucking industry in the 1930s, and have been in continuous use in LTL (less than truckload) operations ever since. The US Military began utilizing cross-dock operations in the 1950s. Wal-Mart began utilizing cross-docking in the retail sector in the late 1980s.In the LTL trucking industry, cross-docking is done by moving cargo from one transport vehicle directly into another, with minimal or no warehousing. In retail practice, cross-docking operations may utilize staging areas where inbound materials are sorted, consolidated, and stored until the outbound shipment is complete and ready to ship.

Advantages of Retail Cross-Docking

- Streamlines the supply chain from point of origin to point of sale

- Reduces handling costs, operating costs, and the storage of inventory

- Products get to the distributor and consequently to the customer faster

- Reduces, or eliminates warehousing costs

- May increase available retail sales space.

[edit]Typical applications

- "Hub and spoke" arrangements, where materials are brought in to one central location and then sorted for delivery to a variety of destinations

- Consolidation arrangements, where a variety of smaller shipments are combined into one larger shipment for economy of transport

- Deconsolidation arrangements, where large shipments (e.g. railcar lots) are broken down into smaller lots for ease of delivery.

Retail cross-dock example: Using the cross-dock technique, Wal-Mart was able to effectively leverage their logistical volume into a core strategic competency.- Wal Mart operates an extensive satellite network of distribution centers serviced by company owned trucks

- Wal Mart’s satellite network sends point of sale (POS) data directly to 4,000 vendors.

- Each register is directly connected to a satellite system sending sales information to Wal Mart’s headquarters and distribution centers.

[edit]Factors influencing the use of retail crossdocks

- Cross-docking is dependent on continuous communication between suppliers, distribution centers, and all points of sale.

- Customer and supplier geography -- particularly when a single corporate customer has many multiple branches or using points

- Freight costs for the commodities being transported

- Cost of inventory in transit

- Complexity of loads

- Handling methods

- Logistics software integration between supplier(s), vendor, and shipper

- Tracking of inventory in transit

[edit]Crossdock facility design

Cross-docks in practice are generally designed in an "I" configuration, which is an elongated rectangle. The goal in using this shape is to maximize the number of inbound and outbound doors that can be added to the facility while the amount of floor space inside the facility to a minimum. In 2004, Bartholdi & Gue demonstrated that this shape is indeed ideal for facilities with 150 doors or less. For facilities with 150-200 doors a "T" shape is more cost effective. Finally, for facilities with 200 or more doors the cost minimizing shape will be an "X".[1][edit]

Customs area:

A customs area is an area designated for storage of commercial goods that have not yet cleared customs. It is surrounded by a customs border. Most international airports and harbours have designated customs areas, sometimes covering the whole facility and including extensive storage warehouses.[1][2]While territorially part of the country of the customs authorities, goods within the customs area have not technically entered the country yet, and may later be subject to customs duties. The goods within the area are also subject to checks regarding their compliance with local rules (for example drug laws andbiosecurity regulations), and thus may be impounded or turned back. For this reason, the customs areas are usually carefully controlled and fenced.The fact that goods are technically still outside the country of the customs area also allows easy transshipment to a third country without the need for customs checks or duties.[1][edit]Other uses

The term is also sometimes used to define an area (usually composed of several countries) which form a customs union, or to describe the area at airports and ports where travellers are checked through customs.

Entrepôt:

An entrepôt (from the French "warehouse") is a trading post where merchandise can be imported and exported without paying import duties, often at a profit. This profit is possible because of trade conditions, for example, the reluctance of ships to travel the entire length of a long trading route, and selling to the entrepôt instead. The entrepôt then sells at a higher price to ships travelling the other segment of the route. As of 2010 this use has mostly been supplanted by customs areas[clarification needed].Entrepôts were especially relevant in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period, when mercantile shipping flourished between Europe and its colonial empires in the Americas and Asia. For example, demand for spices in Europe, coupled with the long trade routes necessary for their delivery, led to a much higher market price than the original buying price. However, traders often did not want to travel the whole route, and thus used the entrepôts on the way to sell on their goods. However, this also led to even more attractive profits for those who persevered to travel the entire route. [1]An example of such an early-modern entrepôt is the 17th-century Amsterdam Entrepôt.

Specific entrepôts- Boma, Congo

- Cap-Vert

- Cape of Good Hope

- Dubai

- Fort Orange, Albany, New York

- Hong Kong

- Naha, Ryūkyū Kingdom

- Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Singapore

Break-of-gauge:

F

Track gauge Broad gauge Standard gauge Narrow gauge Minimum gauge List of rail gauges

Break-of-gauge Dual gauge Gauge conversion Rail tracks Tramway track

With railways, a break-of-gauge occurs where a line of one gauge meets a line of a different gauge. Trains and rolling stock cannot run through without some form of conversion between gauges, and freight and passengers must otherwise be transloaded. Either way, a break-of-gauge adds delays, cost, and inconvenience to traffic that must pass from one gauge to another.

Inconvenience

Transloading of freight from cars of one gauge to cars of another is very labour and time intensive, and increases the risk of damage to goods. If the capacity of freight cars on each system does not match, additional inefficiencies can arise. Technical solutions to avoid transloading include variable gauge axles, replacing the bogies of cars, and the use of transporter cars that can carry a car of a different gauge.Talgo and CAF have developed dual gauge axles (variable gauge axles) which permit through running between broad gauge and standard gauge. In Japan theGauge Change Train has been built on Talgo patents[citation needed] that can run on standard and narrow (1067 mm) gauge.In some cases, breaks-of-gauge are avoided by installing dual gauge track, either permanently or as part of a project to replace one gauge with another.At almost every break-of-gauge, passengers have to change trains, but there are a few passenger trains that can run through a break-of-gauge. For example, the Talgo (variable gauge axles, see above), and the Moscow-Beijing trains (bogie exchange) although on the latter passengers usually have to leave the train for some time whilst the work is done.[edit]Advantages

An advantage is that invading armies may be severely hampered (as when Germany invaded the USSR in WWII).Another advantage might be that if the different gauges have different loading gauges, the break of gauge helps keep the larger wagons clear of smaller tunnels.[edit]Passengers

For passengers trains the inconvenience is less, especially if it is at a major train station, where many passengers change trains or end their journey anyway. Therefore some passenger-only railways have been built with other gauges than would otherwise be used in a country, like the high-speed railways in Japan and Spain.For night trains, which are very common in places like Russia, train change is less desired, especially by night. For these often the bogies are replaced, even if it takes much more time than having the passengers change trains.[edit]Tidal traffic

The inefficiencies of a break of gauge are especially apparent when there is a tide of traffic in one direction, as might happen when fodder from a drought-free region needs to be transhipped to a drought-affected region on the other gauge. Firstly, one might run out of suitable wagons on the other gauge, while loaded wagons unable to be transhipped obstruct the main lines or crossing loops on the first gauge.[edit]Overcoming a break of gauge

Where trains encounter a different gauge, such as at the Spanish-French border or the Russian-Chinese one, the traditional solution has always been transshipment — transferring passengers and freight to cars on the other system. This is obviously far from optimal, and a number of more efficient schemes have been devised. One common one is to build cars to the smaller of the two systems'loading gauges with bogies that are easily removed and replaced, with a bogie exchange at an interchange location on the border. This takes a few minutes per car, but is quicker than transshipment. A more modern and sophisticated method is to have multigauge bogies whose wheels can be moved inward and outward. Normally they are locked in place, but special equipment at the border unlocks the wheels and pushes them inward or outward to the new gauge, relocking the wheels when done. This can be done as the train moves slowly over special equipment.When transhipping from one gauge to another, chances are that the quantity of rolling stock on each gauge is unbalanced, leading to more idle rolling stock on one gauge than other.In some cases, breaks of gauge are avoided by installing dual gauge track, either permanently or as part of a changeover process to a single gauge.[edit]Piggyback operation

One method of achieving interoperability between rolling stock of different gauges, is to piggyback stock of one gauge on special transporter wagons or even ordinary flat wagons fitted with rails. This enables rolling stock to reach workshops and other lines of the same gauge to which they are not otherwise connected. Piggyback operation by the trainload occurred as a temporary measure betweenPort Augusta and Marree during gauge conversion works in the 1950s, to bypass steep gradients and washaways in the Flinders Ranges.Narrow gauge railways were favoured in the underground slate quarries of North Wales, as tunnels could be smaller. The Padarn Railway operated transporter wagons on their 4 ft (1,219 mm) gauge railway, each carrying four 1 ft 10 3⁄4 in (578 mm) slate trams. When the Great Western Railway acquired one of the narrow gauge lines in Blaenau Ffestiniog, they used a similar type of transporter wagon in order to use the quarries' existing slate wagons.[1]Transporter wagons are most commonly used to transport narrow gauge stock over standard gauge lines. More rarely, standard gauge vehicles are carried over narrow gauge tracks using adaptor vehicles; examples include the Rollbocke transporter wagon arrangements in Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic and the milk transporter wagons of the Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railwayin England.In 2010, Japan is developing the Train on Train piggyback concept.[edit]Containerisation

The widespread use of containers since the 1960s has made break of gauge less of a problem, since containers are efficiently transferred from one mode to another by suitable large cranes.Consider the transfer from a train of one gauge to another train of a different gauge. It helps if the lengths of the wagons on each gauge are the same so the containers can be transferred from one train to the other with no transverse movement along the train. The different wagons should carry the same number of containers. Delays to each train depends on how many cranes can operate simultaneously.Container cranes are relatively portable, so that if the break of gauge transshipment hub changes from time to time, the cranes can be moved around as required. Fork lift trucks can also be used.There is a gauge transshipment station at Kidatu in Tanzania.[edit]Examples of breaks of gauge

Some examples of breaks of gauge between systems include:[edit]Africa

- Rail lines linked by ferries on convenient rivers or lakes. See train ferries.

- Dar es Salaam is one of the few places in Africa where different gauges actually meet.

- Kidatu in Tanzania has a container transshipment facility to move freight containers between TAZARA (1067 mm) and Tanzania Railways Corporation trains (1000 mm)

- Angola originally had 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in), 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, but the 1,000 mm and 600 mm lines were converted to 1,067 mm in the 1950s in expectation that the lines would meet, but this has never happened.

- DRCongo originally had both 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, but when these lines met in the 1950s, the 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) line was converted to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm).

[edit]Asia

[edit]Bangladesh

Bangladesh has decided to resolve most of its break-of-gauge problem by converting most of its broad and narrow gauge tracks to dual gauge.[edit]China

China has a standard gauge network; neighbouring countries Mongolia, Russia and Kazakhstan use 1520 mm and Vietnam uses metre gauge, so there are some breaks of gauge. See the Trans-Manchurian Railway (gauge changing at Zabaikalsk on the Russian side of the border), the Trans-Mongolian Railway and the Lanxin railway. Dual gauge reaches into Vietnam as far as Hanoi.[2] There is currently a break of gauge at Dostyk on the Kazakh border, but Kazakhstan is building an additional line, in standard gauge, line between Dostyk and Aktogay[3]

[edit]Hong Kong

Hong Kong's railway, the MTR, has 1,432 mm gauge for its original network, whereas its East Rail Line, West Rail Line and Ma On Shan Line use the standard gauge.[citation needed] The standard gauge lines are leased from another railway company, the KCR Corporation.[citation needed] The Light Rail is also standard gauge.[citation needed][edit]India

Indian Railways has decided to convert a significant proportion of its metre gauge and narrow gauge systems to broad gauge. This is called Project unigauge.[edit]Iran

Iran, with its standard gauge rail system, has break-of-gauge at the borders with Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, and now also has a new break-of-gauge with Pakistan at Zahedan. Pakistan has a broad gauge railway system.The break-of-gauge station at Zahedan was built outside the city, as the existing station was hemmed in by built up areas.[4][dead link][edit]Japan

Most high speed lines in Japan have been built as standard gauge lines. A few routes have been planned as narrow-gauge, and the conventional (non-high-speed) is mostly narrow gauge3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm), so there are some breaks of gauge and dual gauge is used in some places. Private railways often use other gauges.In 2010, Hokkaidō Railway Company was working on a transporter train by trainload concept called Train on Train to carry narrow gauge freight trains at faster speeds on standard gauge flatcars.[edit]North Korea

A break of gauge occurs across the Tumen River which forms the border between North Korea and Russia.[edit]Taiwan (Republic of China)

Like Japan, the Republic of China use the 1,067 mm gauge for the majority of its railway network, but 1,435 mm standard gauge for high-speed rail; however, gauge differences are less of a problem as Taiwan High Speed Rail generally uses separate rolling stock and separate rights of way.[edit]Thailand

Several countries bordering Thailand use meter gauge track, but there are missing links between Thailand and Vietnam via Cambodia.[edit]Europe

[edit]Russian gauge meeting Standard gauge

- vs. Former Soviet Union countries: Russia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova (1,520 mm). Night trains are common, and they are often bogie-exchanged.

- Finland (1,524 mm) and Sweden (1,435 mm), between Tornio and Haparanda via a short dual-gauge bridge. Freight is generally transloaded. No passenger trains. There is also a SeaRail ferry (with 1,435 mm onboard) linking Turku, Finland with Stockholm, Sweden;[5] the Turku terminal handles both gauges.[6]

- Bulgaria (1,435 mm) railroad ferries to Ukraine, Russia and Georgia (1,520 mm)

- Germany (1,435 mm) railroad ferries (with 1,520 mm onboard) to Finland, Russia and Baltic States (1,520 mm)

- While breaks of gauge are generally located near borders, a line carrying iron ore from Ukraine extends into Slovakian territory to a steelworks near Košice[7] and there are plans to extend the line further west, to Vienna.[8] See also Rail gauge in Slovakia.

[edit]Other breaks-of-gauges

- France (1,435 mm) and Spain (1,668 mm), for example at Cerbère (FR) - Portbou (ES); Hendaye (FR) - Irun (ES) and Latour-de-Carol. From 2010 the Spanish high-speed network (1,435 mm) is connected to the French railways without a break-of gauge.

- Switzerland, see "Minor breaks of gauge" section below.

[edit]Oceania

[edit]Australia

- Queensland (3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm)) and New South Wales (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm))

- New South Wales (1,435 mm) and Victoria (5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm))

- Southern South Australia uses broad gauge, like Victoria. Northern South Australia had a number of narrow gauge 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, leading to several break-of-gauge stations at various times including Hamley Bridge, Terowie, Peterborough, Gladstone, Port Pirie, Port Augusta, Marree, Wolseleyand Mount Gambier.

- In the latter part of the 20th century, all mainland capital cities were connected by a standard gauge 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) network, leading to more breaks of gauge (or branch line closures) in states where this is not the norm

- Perth's railway system is narrow gauge (3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm)), while the Indian Pacific is standard gauge. The line between East Perth and Midland, the eastern suburban terminus, and inland to the major rail junction at Northam is dual gauge. All rail east of this is standard gauge.

- Since the 1990s, new concrete sleepers installed in the Adelaide suburban area have been gauge convertible (the difference between the gauges are too close to allow dual gauge).

- In May 2008, agreement reached to convert the declining trafficked broad gauge line of a BG/SG pair for 200 km between Seymour and Albury to double track Standard gauge for growing interstate traffic.

- Since the 1930s, most Victoria steam locomotives were designed for ease of conversion to standard gauge, but except for R766, this has never happened.[9]

- Note that the lines of the same gauge do not all join up, being separated by other gauges, deserts or oceans. Rolling stock is often transferred on low-loaders or by ship.

[edit]Military

Military depots where arms, fuel, etc. are stored are best located at break-of-gauge stations so that stores can be loaded onto the correct gauge directly. Such depots were created at Albury, Tocumwal, amongst others.[edit]New Zealand

New Zealand originally has small lengths of lines of 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in), 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) and 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in), but quickly converted to 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) which better suited this sparsely populated and mountainous country.[edit]North America

- The United States of America had broad, narrow and standard gauge tracks in the 19th century, but is now almost entirely 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge. Narrow-gauge operations are generally isolated rail systems. The notable exception would be the break-of-gauge in Antonito, Colorado between the standard gauge Rio Grande Scenic Railroad and the narrow gauge Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad, billed as the Toltec Gorge Limited.

- Similarly, Canada and Mexico are standard gauge.

- A break-of-gauge, 3 ft (914 mm) to 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm), between Mexico and Guatemala is currently closed.

[edit]South America

- Argentina and Chile both use 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) broad gauge tracks, but the link railway uses 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) narrow gauge with rack railway sections. So there are two break-of-gauge stations, one at Los Andes, Chile and the other at Mendoza, Argentina. It was planned to reopen this currently closed railway in summer 2007 and re-gauge from small to broad to be in future without break-of-gauge

- A break-of-gauge between Argentina and Brazil, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) to 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in)

- A break-of-gauge between Uruguay and Brazil, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) to 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) at Santana do Livramento.

[edit]Minor breaks of gauge

Wherever there are narrow gauge lines that connect with a standard gauge line, there is technically a break-of-gauge. If the amount of traffic transferred between lines is small, this might be a small inconvenience only. In Austria and Switzerland there are numerous breaks-of-gauge between standard-gauge main lines and narrow-gauge railways.The line between Finland and Russia has a minor break-of-gauge. Finnish gauge is 1524 mm and Russian 1520 mm, but this does not stop through-running.The effects of a minor break-of-gauge can be minimized by placing it at the point where a cargo must be removed from cars anyway. An example of this is the East Broad Top Railroad in the United States of America, which had a coal wash and preparation plant at its break-of-gauge in Mount Union, Pennsylvania. The coal was unloaded from narrow gauge cars of the EBT, and after processing was loaded into standard gauge cars of the Pennsylvania Railroad.[edit]Gauge orphan

When a main line is converted to a different gauge, such as with Unigauge in India, branch lines can be cut off and made relatively useless, at least for freight trains, until they too are converted to the new gauge. These severed branches can be called gauge orphans.[edit]Gauge outreach

The opposite of a gauge orphan is a line of one gauge which reaches into the territory composed mainly of another gauge. Examples include five broad gauge lines of Victoria which crossed the border into otherwise standard gauge New South Wales. Similarly the standard gauge line from Albury to Melbourne in 1962 which eliminated most transshipment at Albury, especially the need for passengers to change trains in the middle of the night. A Russian broad gauge line reaches out from Ukraine into Slovakia to carry minerals; another broad gauge line reaches also from Ukraine into Poland to carry heavy iron ore and steel products without the need for transshipment as would be the case if there were a break of gauge at the border. In 2008, it was proposed to extend the Slovak line to Vienna.[10]The gauge outreach from Kalgoorlie to Perth, Western Australia partly replaced the original narrow gauge line, and partly rebuilt that line with better curves and gradients at double dual gauge.In 2010, a proposal surfaced to build a broad gauge line from an iron ore mine at Kaunisvaara in Sweden (whose rail network is otherwise standard gauge) to Finland which has a broad gauge network.[11][edit]

Cross-docking:

Cross-docking is a practice in logistics of unloading materials from an incoming semi-trailer truck or rail car and loading these materials directly into outbound trucks, trailers, or rail cars, with little or no storage in between. This may be done to change type of conveyance, to sort material intended for different destinations, or to combine material from different origins into transport vehicles (or containers) with the same, or similar destination.

Cross-Dock operations were first pioneered in the US trucking industry in the 1930s, and have been in continuous use in LTL (less than truckload) operations ever since. The US Military began utilizing cross-dock operations in the 1950s. Wal-Mart began utilizing cross-docking in the retail sector in the late 1980s.

In the LTL trucking industry, cross-docking is done by moving cargo from one transport vehicle directly into another, with minimal or no warehousing. In retail practice, cross-docking operations may utilize staging areas where inbound materials are sorted, consolidated, and stored until the outbound shipment is complete and ready to ship.

Advantages of Retail Cross-Docking

- Streamlines the supply chain from point of origin to point of sale

- Reduces handling costs, operating costs, and the storage of inventory

- Products get to the distributor and consequently to the customer faster

- Reduces, or eliminates warehousing costs

- May increase available retail sales space.

[edit]Typical applications

- "Hub and spoke" arrangements, where materials are brought in to one central location and then sorted for delivery to a variety of destinations

- Consolidation arrangements, where a variety of smaller shipments are combined into one larger shipment for economy of transport

- Deconsolidation arrangements, where large shipments (e.g. railcar lots) are broken down into smaller lots for ease of delivery.

Retail cross-dock example: Using the cross-dock technique, Wal-Mart was able to effectively leverage their logistical volume into a core strategic competency.

- Wal Mart operates an extensive satellite network of distribution centers serviced by company owned trucks

- Wal Mart’s satellite network sends point of sale (POS) data directly to 4,000 vendors.

- Each register is directly connected to a satellite system sending sales information to Wal Mart’s headquarters and distribution centers.

[edit]Factors influencing the use of retail crossdocks

- Cross-docking is dependent on continuous communication between suppliers, distribution centers, and all points of sale.

- Customer and supplier geography -- particularly when a single corporate customer has many multiple branches or using points

- Freight costs for the commodities being transported

- Cost of inventory in transit

- Complexity of loads

- Handling methods

- Logistics software integration between supplier(s), vendor, and shipper

- Tracking of inventory in transit

[edit]Crossdock facility design

Cross-docks in practice are generally designed in an "I" configuration, which is an elongated rectangle. The goal in using this shape is to maximize the number of inbound and outbound doors that can be added to the facility while the amount of floor space inside the facility to a minimum. In 2004, Bartholdi & Gue demonstrated that this shape is indeed ideal for facilities with 150 doors or less. For facilities with 150-200 doors a "T" shape is more cost effective. Finally, for facilities with 200 or more doors the cost minimizing shape will be an "X".[1]

[edit]

Customs area:

A customs area is an area designated for storage of commercial goods that have not yet cleared customs. It is surrounded by a customs border. Most international airports and harbours have designated customs areas, sometimes covering the whole facility and including extensive storage warehouses.[1][2]While territorially part of the country of the customs authorities, goods within the customs area have not technically entered the country yet, and may later be subject to customs duties. The goods within the area are also subject to checks regarding their compliance with local rules (for example drug laws andbiosecurity regulations), and thus may be impounded or turned back. For this reason, the customs areas are usually carefully controlled and fenced.The fact that goods are technically still outside the country of the customs area also allows easy transshipment to a third country without the need for customs checks or duties.[1][edit]Other uses

The term is also sometimes used to define an area (usually composed of several countries) which form a customs union, or to describe the area at airports and ports where travellers are checked through customs.

Entrepôt:

An entrepôt (from the French "warehouse") is a trading post where merchandise can be imported and exported without paying import duties, often at a profit. This profit is possible because of trade conditions, for example, the reluctance of ships to travel the entire length of a long trading route, and selling to the entrepôt instead. The entrepôt then sells at a higher price to ships travelling the other segment of the route. As of 2010 this use has mostly been supplanted by customs areas[clarification needed].Entrepôts were especially relevant in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period, when mercantile shipping flourished between Europe and its colonial empires in the Americas and Asia. For example, demand for spices in Europe, coupled with the long trade routes necessary for their delivery, led to a much higher market price than the original buying price. However, traders often did not want to travel the whole route, and thus used the entrepôts on the way to sell on their goods. However, this also led to even more attractive profits for those who persevered to travel the entire route. [1]An example of such an early-modern entrepôt is the 17th-century Amsterdam Entrepôt.

Specific entrepôts- Boma, Congo

- Cap-Vert

- Cape of Good Hope

- Dubai

- Fort Orange, Albany, New York

- Hong Kong

- Naha, Ryūkyū Kingdom

- Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Singapore

Break-of-gauge:

F

Track gauge Broad gauge Standard gauge Narrow gauge Minimum gauge List of rail gauges

Break-of-gauge Dual gauge Gauge conversion Rail tracks Tramway track

With railways, a break-of-gauge occurs where a line of one gauge meets a line of a different gauge. Trains and rolling stock cannot run through without some form of conversion between gauges, and freight and passengers must otherwise be transloaded. Either way, a break-of-gauge adds delays, cost, and inconvenience to traffic that must pass from one gauge to another.

Inconvenience

Transloading of freight from cars of one gauge to cars of another is very labour and time intensive, and increases the risk of damage to goods. If the capacity of freight cars on each system does not match, additional inefficiencies can arise. Technical solutions to avoid transloading include variable gauge axles, replacing the bogies of cars, and the use of transporter cars that can carry a car of a different gauge.Talgo and CAF have developed dual gauge axles (variable gauge axles) which permit through running between broad gauge and standard gauge. In Japan theGauge Change Train has been built on Talgo patents[citation needed] that can run on standard and narrow (1067 mm) gauge.In some cases, breaks-of-gauge are avoided by installing dual gauge track, either permanently or as part of a project to replace one gauge with another.At almost every break-of-gauge, passengers have to change trains, but there are a few passenger trains that can run through a break-of-gauge. For example, the Talgo (variable gauge axles, see above), and the Moscow-Beijing trains (bogie exchange) although on the latter passengers usually have to leave the train for some time whilst the work is done.[edit]Advantages

An advantage is that invading armies may be severely hampered (as when Germany invaded the USSR in WWII).Another advantage might be that if the different gauges have different loading gauges, the break of gauge helps keep the larger wagons clear of smaller tunnels.[edit]Passengers

For passengers trains the inconvenience is less, especially if it is at a major train station, where many passengers change trains or end their journey anyway. Therefore some passenger-only railways have been built with other gauges than would otherwise be used in a country, like the high-speed railways in Japan and Spain.For night trains, which are very common in places like Russia, train change is less desired, especially by night. For these often the bogies are replaced, even if it takes much more time than having the passengers change trains.[edit]Tidal traffic

The inefficiencies of a break of gauge are especially apparent when there is a tide of traffic in one direction, as might happen when fodder from a drought-free region needs to be transhipped to a drought-affected region on the other gauge. Firstly, one might run out of suitable wagons on the other gauge, while loaded wagons unable to be transhipped obstruct the main lines or crossing loops on the first gauge.[edit]Overcoming a break of gauge

Where trains encounter a different gauge, such as at the Spanish-French border or the Russian-Chinese one, the traditional solution has always been transshipment — transferring passengers and freight to cars on the other system. This is obviously far from optimal, and a number of more efficient schemes have been devised. One common one is to build cars to the smaller of the two systems'loading gauges with bogies that are easily removed and replaced, with a bogie exchange at an interchange location on the border. This takes a few minutes per car, but is quicker than transshipment. A more modern and sophisticated method is to have multigauge bogies whose wheels can be moved inward and outward. Normally they are locked in place, but special equipment at the border unlocks the wheels and pushes them inward or outward to the new gauge, relocking the wheels when done. This can be done as the train moves slowly over special equipment.When transhipping from one gauge to another, chances are that the quantity of rolling stock on each gauge is unbalanced, leading to more idle rolling stock on one gauge than other.In some cases, breaks of gauge are avoided by installing dual gauge track, either permanently or as part of a changeover process to a single gauge.[edit]Piggyback operation

One method of achieving interoperability between rolling stock of different gauges, is to piggyback stock of one gauge on special transporter wagons or even ordinary flat wagons fitted with rails. This enables rolling stock to reach workshops and other lines of the same gauge to which they are not otherwise connected. Piggyback operation by the trainload occurred as a temporary measure betweenPort Augusta and Marree during gauge conversion works in the 1950s, to bypass steep gradients and washaways in the Flinders Ranges.Narrow gauge railways were favoured in the underground slate quarries of North Wales, as tunnels could be smaller. The Padarn Railway operated transporter wagons on their 4 ft (1,219 mm) gauge railway, each carrying four 1 ft 10 3⁄4 in (578 mm) slate trams. When the Great Western Railway acquired one of the narrow gauge lines in Blaenau Ffestiniog, they used a similar type of transporter wagon in order to use the quarries' existing slate wagons.[1]Transporter wagons are most commonly used to transport narrow gauge stock over standard gauge lines. More rarely, standard gauge vehicles are carried over narrow gauge tracks using adaptor vehicles; examples include the Rollbocke transporter wagon arrangements in Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic and the milk transporter wagons of the Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railwayin England.In 2010, Japan is developing the Train on Train piggyback concept.[edit]Containerisation

The widespread use of containers since the 1960s has made break of gauge less of a problem, since containers are efficiently transferred from one mode to another by suitable large cranes.Consider the transfer from a train of one gauge to another train of a different gauge. It helps if the lengths of the wagons on each gauge are the same so the containers can be transferred from one train to the other with no transverse movement along the train. The different wagons should carry the same number of containers. Delays to each train depends on how many cranes can operate simultaneously.Container cranes are relatively portable, so that if the break of gauge transshipment hub changes from time to time, the cranes can be moved around as required. Fork lift trucks can also be used.There is a gauge transshipment station at Kidatu in Tanzania.[edit]Examples of breaks of gauge

Some examples of breaks of gauge between systems include:[edit]Africa

- Rail lines linked by ferries on convenient rivers or lakes. See train ferries.

- Dar es Salaam is one of the few places in Africa where different gauges actually meet.

- Kidatu in Tanzania has a container transshipment facility to move freight containers between TAZARA (1067 mm) and Tanzania Railways Corporation trains (1000 mm)

- Angola originally had 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in), 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, but the 1,000 mm and 600 mm lines were converted to 1,067 mm in the 1950s in expectation that the lines would meet, but this has never happened.

- DRCongo originally had both 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, but when these lines met in the 1950s, the 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) line was converted to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm).

[edit]Asia

[edit]Bangladesh

Bangladesh has decided to resolve most of its break-of-gauge problem by converting most of its broad and narrow gauge tracks to dual gauge.[edit]China

China has a standard gauge network; neighbouring countries Mongolia, Russia and Kazakhstan use 1520 mm and Vietnam uses metre gauge, so there are some breaks of gauge. See the Trans-Manchurian Railway (gauge changing at Zabaikalsk on the Russian side of the border), the Trans-Mongolian Railway and the Lanxin railway. Dual gauge reaches into Vietnam as far as Hanoi.[2] There is currently a break of gauge at Dostyk on the Kazakh border, but Kazakhstan is building an additional line, in standard gauge, line between Dostyk and Aktogay[3]

[edit]Hong Kong

Hong Kong's railway, the MTR, has 1,432 mm gauge for its original network, whereas its East Rail Line, West Rail Line and Ma On Shan Line use the standard gauge.[citation needed] The standard gauge lines are leased from another railway company, the KCR Corporation.[citation needed] The Light Rail is also standard gauge.[citation needed][edit]India

Indian Railways has decided to convert a significant proportion of its metre gauge and narrow gauge systems to broad gauge. This is called Project unigauge.[edit]Iran

Iran, with its standard gauge rail system, has break-of-gauge at the borders with Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, and now also has a new break-of-gauge with Pakistan at Zahedan. Pakistan has a broad gauge railway system.The break-of-gauge station at Zahedan was built outside the city, as the existing station was hemmed in by built up areas.[4][dead link][edit]Japan

Most high speed lines in Japan have been built as standard gauge lines. A few routes have been planned as narrow-gauge, and the conventional (non-high-speed) is mostly narrow gauge3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm), so there are some breaks of gauge and dual gauge is used in some places. Private railways often use other gauges.In 2010, Hokkaidō Railway Company was working on a transporter train by trainload concept called Train on Train to carry narrow gauge freight trains at faster speeds on standard gauge flatcars.[edit]North Korea

A break of gauge occurs across the Tumen River which forms the border between North Korea and Russia.[edit]Taiwan (Republic of China)

Like Japan, the Republic of China use the 1,067 mm gauge for the majority of its railway network, but 1,435 mm standard gauge for high-speed rail; however, gauge differences are less of a problem as Taiwan High Speed Rail generally uses separate rolling stock and separate rights of way.[edit]Thailand

Several countries bordering Thailand use meter gauge track, but there are missing links between Thailand and Vietnam via Cambodia.[edit]Europe

[edit]Russian gauge meeting Standard gauge

- vs. Former Soviet Union countries: Russia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova (1,520 mm). Night trains are common, and they are often bogie-exchanged.

- Finland (1,524 mm) and Sweden (1,435 mm), between Tornio and Haparanda via a short dual-gauge bridge. Freight is generally transloaded. No passenger trains. There is also a SeaRail ferry (with 1,435 mm onboard) linking Turku, Finland with Stockholm, Sweden;[5] the Turku terminal handles both gauges.[6]

- Bulgaria (1,435 mm) railroad ferries to Ukraine, Russia and Georgia (1,520 mm)

- Germany (1,435 mm) railroad ferries (with 1,520 mm onboard) to Finland, Russia and Baltic States (1,520 mm)

- While breaks of gauge are generally located near borders, a line carrying iron ore from Ukraine extends into Slovakian territory to a steelworks near Košice[7] and there are plans to extend the line further west, to Vienna.[8] See also Rail gauge in Slovakia.

[edit]Other breaks-of-gauges

- France (1,435 mm) and Spain (1,668 mm), for example at Cerbère (FR) - Portbou (ES); Hendaye (FR) - Irun (ES) and Latour-de-Carol. From 2010 the Spanish high-speed network (1,435 mm) is connected to the French railways without a break-of gauge.

- Switzerland, see "Minor breaks of gauge" section below.

[edit]Oceania

[edit]Australia

- Queensland (3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm)) and New South Wales (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm))

- New South Wales (1,435 mm) and Victoria (5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm))

- Southern South Australia uses broad gauge, like Victoria. Northern South Australia had a number of narrow gauge 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, leading to several break-of-gauge stations at various times including Hamley Bridge, Terowie, Peterborough, Gladstone, Port Pirie, Port Augusta, Marree, Wolseleyand Mount Gambier.

- In the latter part of the 20th century, all mainland capital cities were connected by a standard gauge 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) network, leading to more breaks of gauge (or branch line closures) in states where this is not the norm

- Perth's railway system is narrow gauge (3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm)), while the Indian Pacific is standard gauge. The line between East Perth and Midland, the eastern suburban terminus, and inland to the major rail junction at Northam is dual gauge. All rail east of this is standard gauge.

- Since the 1990s, new concrete sleepers installed in the Adelaide suburban area have been gauge convertible (the difference between the gauges are too close to allow dual gauge).

- In May 2008, agreement reached to convert the declining trafficked broad gauge line of a BG/SG pair for 200 km between Seymour and Albury to double track Standard gauge for growing interstate traffic.

- Since the 1930s, most Victoria steam locomotives were designed for ease of conversion to standard gauge, but except for R766, this has never happened.[9]

- Note that the lines of the same gauge do not all join up, being separated by other gauges, deserts or oceans. Rolling stock is often transferred on low-loaders or by ship.

[edit]Military

Military depots where arms, fuel, etc. are stored are best located at break-of-gauge stations so that stores can be loaded onto the correct gauge directly. Such depots were created at Albury, Tocumwal, amongst others.[edit]New Zealand

New Zealand originally has small lengths of lines of 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in), 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) and 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in), but quickly converted to 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) which better suited this sparsely populated and mountainous country.[edit]North America

- The United States of America had broad, narrow and standard gauge tracks in the 19th century, but is now almost entirely 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge. Narrow-gauge operations are generally isolated rail systems. The notable exception would be the break-of-gauge in Antonito, Colorado between the standard gauge Rio Grande Scenic Railroad and the narrow gauge Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad, billed as the Toltec Gorge Limited.

- Similarly, Canada and Mexico are standard gauge.

- A break-of-gauge, 3 ft (914 mm) to 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm), between Mexico and Guatemala is currently closed.

[edit]South America

- Argentina and Chile both use 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) broad gauge tracks, but the link railway uses 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) narrow gauge with rack railway sections. So there are two break-of-gauge stations, one at Los Andes, Chile and the other at Mendoza, Argentina. It was planned to reopen this currently closed railway in summer 2007 and re-gauge from small to broad to be in future without break-of-gauge

- A break-of-gauge between Argentina and Brazil, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) to 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in)

- A break-of-gauge between Uruguay and Brazil, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) to 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) at Santana do Livramento.

[edit]Minor breaks of gauge

Wherever there are narrow gauge lines that connect with a standard gauge line, there is technically a break-of-gauge. If the amount of traffic transferred between lines is small, this might be a small inconvenience only. In Austria and Switzerland there are numerous breaks-of-gauge between standard-gauge main lines and narrow-gauge railways.The line between Finland and Russia has a minor break-of-gauge. Finnish gauge is 1524 mm and Russian 1520 mm, but this does not stop through-running.The effects of a minor break-of-gauge can be minimized by placing it at the point where a cargo must be removed from cars anyway. An example of this is the East Broad Top Railroad in the United States of America, which had a coal wash and preparation plant at its break-of-gauge in Mount Union, Pennsylvania. The coal was unloaded from narrow gauge cars of the EBT, and after processing was loaded into standard gauge cars of the Pennsylvania Railroad.[edit]Gauge orphan

When a main line is converted to a different gauge, such as with Unigauge in India, branch lines can be cut off and made relatively useless, at least for freight trains, until they too are converted to the new gauge. These severed branches can be called gauge orphans.[edit]Gauge outreach

The opposite of a gauge orphan is a line of one gauge which reaches into the territory composed mainly of another gauge. Examples include five broad gauge lines of Victoria which crossed the border into otherwise standard gauge New South Wales. Similarly the standard gauge line from Albury to Melbourne in 1962 which eliminated most transshipment at Albury, especially the need for passengers to change trains in the middle of the night. A Russian broad gauge line reaches out from Ukraine into Slovakia to carry minerals; another broad gauge line reaches also from Ukraine into Poland to carry heavy iron ore and steel products without the need for transshipment as would be the case if there were a break of gauge at the border. In 2008, it was proposed to extend the Slovak line to Vienna.[10]The gauge outreach from Kalgoorlie to Perth, Western Australia partly replaced the original narrow gauge line, and partly rebuilt that line with better curves and gradients at double dual gauge.In 2010, a proposal surfaced to build a broad gauge line from an iron ore mine at Kaunisvaara in Sweden (whose rail network is otherwise standard gauge) to Finland which has a broad gauge network.[11][edit]

Customs area:

A customs area is an area designated for storage of commercial goods that have not yet cleared customs. It is surrounded by a customs border. Most international airports and harbours have designated customs areas, sometimes covering the whole facility and including extensive storage warehouses.[1][2]

While territorially part of the country of the customs authorities, goods within the customs area have not technically entered the country yet, and may later be subject to customs duties. The goods within the area are also subject to checks regarding their compliance with local rules (for example drug laws andbiosecurity regulations), and thus may be impounded or turned back. For this reason, the customs areas are usually carefully controlled and fenced.

The fact that goods are technically still outside the country of the customs area also allows easy transshipment to a third country without the need for customs checks or duties.[1]

[edit]Other uses

The term is also sometimes used to define an area (usually composed of several countries) which form a customs union, or to describe the area at airports and ports where travellers are checked through customs.

Entrepôt:

An entrepôt (from the French "warehouse") is a trading post where merchandise can be imported and exported without paying import duties, often at a profit. This profit is possible because of trade conditions, for example, the reluctance of ships to travel the entire length of a long trading route, and selling to the entrepôt instead. The entrepôt then sells at a higher price to ships travelling the other segment of the route. As of 2010 this use has mostly been supplanted by customs areas[clarification needed].

Entrepôts were especially relevant in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period, when mercantile shipping flourished between Europe and its colonial empires in the Americas and Asia. For example, demand for spices in Europe, coupled with the long trade routes necessary for their delivery, led to a much higher market price than the original buying price. However, traders often did not want to travel the whole route, and thus used the entrepôts on the way to sell on their goods. However, this also led to even more attractive profits for those who persevered to travel the entire route. [1]An example of such an early-modern entrepôt is the 17th-century Amsterdam Entrepôt.

Specific entrepôts

- Boma, Congo

- Cap-Vert

- Cape of Good Hope

- Dubai

- Fort Orange, Albany, New York

- Hong Kong

- Naha, Ryūkyū Kingdom

- Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Singapore

Break-of-gauge:

F

| Track gauge |

|---|

| Broad gauge |

| Standard gauge |

| Narrow gauge |

| Minimum gauge |

| List of rail gauges |

| Break-of-gauge |

| Dual gauge |

| Gauge conversion |

| Rail tracks |

| Tramway track |

With railways, a break-of-gauge occurs where a line of one gauge meets a line of a different gauge. Trains and rolling stock cannot run through without some form of conversion between gauges, and freight and passengers must otherwise be transloaded. Either way, a break-of-gauge adds delays, cost, and inconvenience to traffic that must pass from one gauge to another.

Inconvenience

Transloading of freight from cars of one gauge to cars of another is very labour and time intensive, and increases the risk of damage to goods. If the capacity of freight cars on each system does not match, additional inefficiencies can arise. Technical solutions to avoid transloading include variable gauge axles, replacing the bogies of cars, and the use of transporter cars that can carry a car of a different gauge.

Talgo and CAF have developed dual gauge axles (variable gauge axles) which permit through running between broad gauge and standard gauge. In Japan theGauge Change Train has been built on Talgo patents[citation needed] that can run on standard and narrow (1067 mm) gauge.

In some cases, breaks-of-gauge are avoided by installing dual gauge track, either permanently or as part of a project to replace one gauge with another.

At almost every break-of-gauge, passengers have to change trains, but there are a few passenger trains that can run through a break-of-gauge. For example, the Talgo (variable gauge axles, see above), and the Moscow-Beijing trains (bogie exchange) although on the latter passengers usually have to leave the train for some time whilst the work is done.

[edit]Advantages

An advantage is that invading armies may be severely hampered (as when Germany invaded the USSR in WWII).

Another advantage might be that if the different gauges have different loading gauges, the break of gauge helps keep the larger wagons clear of smaller tunnels.

[edit]Passengers

For passengers trains the inconvenience is less, especially if it is at a major train station, where many passengers change trains or end their journey anyway. Therefore some passenger-only railways have been built with other gauges than would otherwise be used in a country, like the high-speed railways in Japan and Spain.

For night trains, which are very common in places like Russia, train change is less desired, especially by night. For these often the bogies are replaced, even if it takes much more time than having the passengers change trains.

[edit]Tidal traffic

The inefficiencies of a break of gauge are especially apparent when there is a tide of traffic in one direction, as might happen when fodder from a drought-free region needs to be transhipped to a drought-affected region on the other gauge. Firstly, one might run out of suitable wagons on the other gauge, while loaded wagons unable to be transhipped obstruct the main lines or crossing loops on the first gauge.

[edit]Overcoming a break of gauge

Where trains encounter a different gauge, such as at the Spanish-French border or the Russian-Chinese one, the traditional solution has always been transshipment — transferring passengers and freight to cars on the other system. This is obviously far from optimal, and a number of more efficient schemes have been devised. One common one is to build cars to the smaller of the two systems'loading gauges with bogies that are easily removed and replaced, with a bogie exchange at an interchange location on the border. This takes a few minutes per car, but is quicker than transshipment. A more modern and sophisticated method is to have multigauge bogies whose wheels can be moved inward and outward. Normally they are locked in place, but special equipment at the border unlocks the wheels and pushes them inward or outward to the new gauge, relocking the wheels when done. This can be done as the train moves slowly over special equipment.

When transhipping from one gauge to another, chances are that the quantity of rolling stock on each gauge is unbalanced, leading to more idle rolling stock on one gauge than other.

In some cases, breaks of gauge are avoided by installing dual gauge track, either permanently or as part of a changeover process to a single gauge.

[edit]Piggyback operation

One method of achieving interoperability between rolling stock of different gauges, is to piggyback stock of one gauge on special transporter wagons or even ordinary flat wagons fitted with rails. This enables rolling stock to reach workshops and other lines of the same gauge to which they are not otherwise connected. Piggyback operation by the trainload occurred as a temporary measure betweenPort Augusta and Marree during gauge conversion works in the 1950s, to bypass steep gradients and washaways in the Flinders Ranges.

Narrow gauge railways were favoured in the underground slate quarries of North Wales, as tunnels could be smaller. The Padarn Railway operated transporter wagons on their 4 ft (1,219 mm) gauge railway, each carrying four 1 ft 10 3⁄4 in (578 mm) slate trams. When the Great Western Railway acquired one of the narrow gauge lines in Blaenau Ffestiniog, they used a similar type of transporter wagon in order to use the quarries' existing slate wagons.[1]

Transporter wagons are most commonly used to transport narrow gauge stock over standard gauge lines. More rarely, standard gauge vehicles are carried over narrow gauge tracks using adaptor vehicles; examples include the Rollbocke transporter wagon arrangements in Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic and the milk transporter wagons of the Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railwayin England.

In 2010, Japan is developing the Train on Train piggyback concept.

[edit]Containerisation

The widespread use of containers since the 1960s has made break of gauge less of a problem, since containers are efficiently transferred from one mode to another by suitable large cranes.

Consider the transfer from a train of one gauge to another train of a different gauge. It helps if the lengths of the wagons on each gauge are the same so the containers can be transferred from one train to the other with no transverse movement along the train. The different wagons should carry the same number of containers. Delays to each train depends on how many cranes can operate simultaneously.

Container cranes are relatively portable, so that if the break of gauge transshipment hub changes from time to time, the cranes can be moved around as required. Fork lift trucks can also be used.

There is a gauge transshipment station at Kidatu in Tanzania.

[edit]Examples of breaks of gauge

Some examples of breaks of gauge between systems include:

[edit]Africa

- Rail lines linked by ferries on convenient rivers or lakes. See train ferries.

- Dar es Salaam is one of the few places in Africa where different gauges actually meet.

- Kidatu in Tanzania has a container transshipment facility to move freight containers between TAZARA (1067 mm) and Tanzania Railways Corporation trains (1000 mm)

- Angola originally had 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in), 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, but the 1,000 mm and 600 mm lines were converted to 1,067 mm in the 1950s in expectation that the lines would meet, but this has never happened.

- DRCongo originally had both 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, but when these lines met in the 1950s, the 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) line was converted to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm).

[edit]Asia

[edit]Bangladesh

Bangladesh has decided to resolve most of its break-of-gauge problem by converting most of its broad and narrow gauge tracks to dual gauge.

[edit]China

China has a standard gauge network; neighbouring countries Mongolia, Russia and Kazakhstan use 1520 mm and Vietnam uses metre gauge, so there are some breaks of gauge. See the Trans-Manchurian Railway (gauge changing at Zabaikalsk on the Russian side of the border), the Trans-Mongolian Railway and the Lanxin railway. Dual gauge reaches into Vietnam as far as Hanoi.[2] There is currently a break of gauge at Dostyk on the Kazakh border, but Kazakhstan is building an additional line, in standard gauge, line between Dostyk and Aktogay[3]

[edit]Hong Kong

Hong Kong's railway, the MTR, has 1,432 mm gauge for its original network, whereas its East Rail Line, West Rail Line and Ma On Shan Line use the standard gauge.[citation needed] The standard gauge lines are leased from another railway company, the KCR Corporation.[citation needed] The Light Rail is also standard gauge.[citation needed]

[edit]India

Indian Railways has decided to convert a significant proportion of its metre gauge and narrow gauge systems to broad gauge. This is called Project unigauge.

[edit]Iran

Iran, with its standard gauge rail system, has break-of-gauge at the borders with Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, and now also has a new break-of-gauge with Pakistan at Zahedan. Pakistan has a broad gauge railway system.

The break-of-gauge station at Zahedan was built outside the city, as the existing station was hemmed in by built up areas.[4][dead link]

[edit]Japan

Most high speed lines in Japan have been built as standard gauge lines. A few routes have been planned as narrow-gauge, and the conventional (non-high-speed) is mostly narrow gauge3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm), so there are some breaks of gauge and dual gauge is used in some places. Private railways often use other gauges.

In 2010, Hokkaidō Railway Company was working on a transporter train by trainload concept called Train on Train to carry narrow gauge freight trains at faster speeds on standard gauge flatcars.

[edit]North Korea

A break of gauge occurs across the Tumen River which forms the border between North Korea and Russia.

[edit]Taiwan (Republic of China)

Like Japan, the Republic of China use the 1,067 mm gauge for the majority of its railway network, but 1,435 mm standard gauge for high-speed rail; however, gauge differences are less of a problem as Taiwan High Speed Rail generally uses separate rolling stock and separate rights of way.

[edit]Thailand

Several countries bordering Thailand use meter gauge track, but there are missing links between Thailand and Vietnam via Cambodia.

[edit]Europe

[edit]Russian gauge meeting Standard gauge

- vs. Former Soviet Union countries: Russia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova (1,520 mm). Night trains are common, and they are often bogie-exchanged.

- Finland (1,524 mm) and Sweden (1,435 mm), between Tornio and Haparanda via a short dual-gauge bridge. Freight is generally transloaded. No passenger trains. There is also a SeaRail ferry (with 1,435 mm onboard) linking Turku, Finland with Stockholm, Sweden;[5] the Turku terminal handles both gauges.[6]

- Bulgaria (1,435 mm) railroad ferries to Ukraine, Russia and Georgia (1,520 mm)

- Germany (1,435 mm) railroad ferries (with 1,520 mm onboard) to Finland, Russia and Baltic States (1,520 mm)

- While breaks of gauge are generally located near borders, a line carrying iron ore from Ukraine extends into Slovakian territory to a steelworks near Košice[7] and there are plans to extend the line further west, to Vienna.[8] See also Rail gauge in Slovakia.

[edit]Other breaks-of-gauges

- France (1,435 mm) and Spain (1,668 mm), for example at Cerbère (FR) - Portbou (ES); Hendaye (FR) - Irun (ES) and Latour-de-Carol. From 2010 the Spanish high-speed network (1,435 mm) is connected to the French railways without a break-of gauge.

- Switzerland, see "Minor breaks of gauge" section below.

[edit]Oceania

[edit]Australia

- Queensland (3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm)) and New South Wales (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm))

- New South Wales (1,435 mm) and Victoria (5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm))

- Southern South Australia uses broad gauge, like Victoria. Northern South Australia had a number of narrow gauge 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines, leading to several break-of-gauge stations at various times including Hamley Bridge, Terowie, Peterborough, Gladstone, Port Pirie, Port Augusta, Marree, Wolseleyand Mount Gambier.

- In the latter part of the 20th century, all mainland capital cities were connected by a standard gauge 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) network, leading to more breaks of gauge (or branch line closures) in states where this is not the norm

- Perth's railway system is narrow gauge (3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm)), while the Indian Pacific is standard gauge. The line between East Perth and Midland, the eastern suburban terminus, and inland to the major rail junction at Northam is dual gauge. All rail east of this is standard gauge.

- Since the 1990s, new concrete sleepers installed in the Adelaide suburban area have been gauge convertible (the difference between the gauges are too close to allow dual gauge).

- In May 2008, agreement reached to convert the declining trafficked broad gauge line of a BG/SG pair for 200 km between Seymour and Albury to double track Standard gauge for growing interstate traffic.

- Since the 1930s, most Victoria steam locomotives were designed for ease of conversion to standard gauge, but except for R766, this has never happened.[9]

- Note that the lines of the same gauge do not all join up, being separated by other gauges, deserts or oceans. Rolling stock is often transferred on low-loaders or by ship.

[edit]Military

Military depots where arms, fuel, etc. are stored are best located at break-of-gauge stations so that stores can be loaded onto the correct gauge directly. Such depots were created at Albury, Tocumwal, amongst others.

[edit]New Zealand

New Zealand originally has small lengths of lines of 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in), 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) and 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in), but quickly converted to 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) which better suited this sparsely populated and mountainous country.

[edit]North America

- The United States of America had broad, narrow and standard gauge tracks in the 19th century, but is now almost entirely 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge. Narrow-gauge operations are generally isolated rail systems. The notable exception would be the break-of-gauge in Antonito, Colorado between the standard gauge Rio Grande Scenic Railroad and the narrow gauge Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad, billed as the Toltec Gorge Limited.

- Similarly, Canada and Mexico are standard gauge.

- A break-of-gauge, 3 ft (914 mm) to 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm), between Mexico and Guatemala is currently closed.

[edit]South America

- Argentina and Chile both use 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) broad gauge tracks, but the link railway uses 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) narrow gauge with rack railway sections. So there are two break-of-gauge stations, one at Los Andes, Chile and the other at Mendoza, Argentina. It was planned to reopen this currently closed railway in summer 2007 and re-gauge from small to broad to be in future without break-of-gauge

- A break-of-gauge between Argentina and Brazil, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) to 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in)

- A break-of-gauge between Uruguay and Brazil, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) to 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) at Santana do Livramento.

[edit]Minor breaks of gauge

Wherever there are narrow gauge lines that connect with a standard gauge line, there is technically a break-of-gauge. If the amount of traffic transferred between lines is small, this might be a small inconvenience only. In Austria and Switzerland there are numerous breaks-of-gauge between standard-gauge main lines and narrow-gauge railways.

The line between Finland and Russia has a minor break-of-gauge. Finnish gauge is 1524 mm and Russian 1520 mm, but this does not stop through-running.

The effects of a minor break-of-gauge can be minimized by placing it at the point where a cargo must be removed from cars anyway. An example of this is the East Broad Top Railroad in the United States of America, which had a coal wash and preparation plant at its break-of-gauge in Mount Union, Pennsylvania. The coal was unloaded from narrow gauge cars of the EBT, and after processing was loaded into standard gauge cars of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

[edit]Gauge orphan

When a main line is converted to a different gauge, such as with Unigauge in India, branch lines can be cut off and made relatively useless, at least for freight trains, until they too are converted to the new gauge. These severed branches can be called gauge orphans.

[edit]Gauge outreach

The opposite of a gauge orphan is a line of one gauge which reaches into the territory composed mainly of another gauge. Examples include five broad gauge lines of Victoria which crossed the border into otherwise standard gauge New South Wales. Similarly the standard gauge line from Albury to Melbourne in 1962 which eliminated most transshipment at Albury, especially the need for passengers to change trains in the middle of the night. A Russian broad gauge line reaches out from Ukraine into Slovakia to carry minerals; another broad gauge line reaches also from Ukraine into Poland to carry heavy iron ore and steel products without the need for transshipment as would be the case if there were a break of gauge at the border. In 2008, it was proposed to extend the Slovak line to Vienna.[10]The gauge outreach from Kalgoorlie to Perth, Western Australia partly replaced the original narrow gauge line, and partly rebuilt that line with better curves and gradients at double dual gauge.

In 2010, a proposal surfaced to build a broad gauge line from an iron ore mine at Kaunisvaara in Sweden (whose rail network is otherwise standard gauge) to Finland which has a broad gauge network.[11]

No comments:

Post a Comment